| Parrotlet Breeders – Pocket Parrots | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breeding Ethics and Standards are #1 ! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

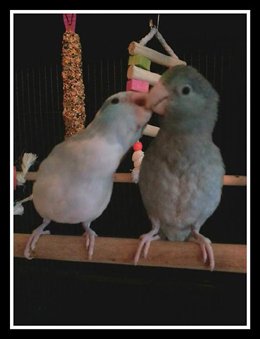

| Proud Members of the International Parrotlet Society. Specializing in Quality Hand-Fed Baby Pacific Parrotlets. ParrotletParrot ParrotletParrots Parrotlet Parrots ParrotletParrotParrotlets – Handfed Babies ParrotletBird Parrotletbirds Parrotlet Birds ParrotletBird  We breed quality Parrotlets not quantity. We breed quality Parrotlets not quantity.Our Breeding Ethics and Standards are #1 ! Our baby Parrotlets – For sale

Green Cheek Conures

Breeding Ethics and Standards are #1 ! Why get your babies from LuckFeathers.com ? We have over 25 years experience, GULF COAST BUDGERIGAR SOCIETY MEMBERS

African Grey Babies Coming Soon!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

![]() Pacific Parrotlet Care & Information

Pacific Parrotlet Care & Information

Also called – Celestial Parrotlet & Lesson’s Parrotlets

About: The worlds smallest Parrot, known as the Tea Cup Parrot, Pocket Parrot and many other catchy names. They are cousin to the large Amazons and their personality shows it. Almost all of their DNA matches the Amazon. They are sometimes called small Amazons and are described as dynamite in small packages. Parrotlets are in a group of the smallest New World parrot species, comprising several genera, namely Forpus, Nannopsittaca, and Touit. They have a stocky build and a broad tail, much like the lovebirds of East Africa and fig parrots and pygmy parrots of Australasia. They are endemic to Middle and South America. The Pacific Parrotlets (Forpus coelestis) – also known as Celestial, Western, Lesson’s or Ridgway’s Parrotlets – occur naturally in Western Ecuador and North-western Peru (on the Pacific coast). They are resident (non-migratory) within their range. These birds inhabit arid lowland scrub and semi-open tropical deciduous woodland.

About: The worlds smallest Parrot, known as the Tea Cup Parrot, Pocket Parrot and many other catchy names. They are cousin to the large Amazons and their personality shows it. Almost all of their DNA matches the Amazon. They are sometimes called small Amazons and are described as dynamite in small packages. Parrotlets are in a group of the smallest New World parrot species, comprising several genera, namely Forpus, Nannopsittaca, and Touit. They have a stocky build and a broad tail, much like the lovebirds of East Africa and fig parrots and pygmy parrots of Australasia. They are endemic to Middle and South America. The Pacific Parrotlets (Forpus coelestis) – also known as Celestial, Western, Lesson’s or Ridgway’s Parrotlets – occur naturally in Western Ecuador and North-western Peru (on the Pacific coast). They are resident (non-migratory) within their range. These birds inhabit arid lowland scrub and semi-open tropical deciduous woodland.

These miniature parrots in the wild travel in flocks which, depending on the species, can range from as low as four to over 100 birds. Most species travel in flocks of about 5–40. They form lifelong and tight pair bonds with their chosen mates.

Parrotlets are the smallest commonly bred Parrot species in captivity. The genus Forpus, particularly the Celestial or Pacific Parrotlet, is growing in availability and popularity in the USA.

The most commonly kept Parrotlet in the USA is by far the Celestial or Pacific Parrotlet. The Mexican Parrotlet, Spectacled Parrotlet, Green-Rumped Parrotlet and Yellow-faced Parrotlet are also fairly common pets. Their popularity as pets has grown due to their small size and large personalities. Parrotlets are commonly known as playful birds that enjoy chewing as much as their larger Amazon counterparts. Being highly intelligent and active parrots, parrotlets must have ample opportunities to play and exercise. Environmental enrichment must be made a part of their lives as to prevent boredom. Parrotlets keep themselves more than occupied when left alone for several hours, so long as they are provided with an array of chewable and destructible toys to play with. However, when their keepers get home, they often greet them with lovely chirps and whistles to let them know they want attention. They can mimic speech with a somewhat impressive vocabulary though their voice is very small. Males mimic better than females do. They can be very territorial inside their cages and may try to bite if a human reaches in, even to feed them. They consider the cage to be their sole territory. But the same bird, when outside his cage, can be very affectionate—flying over to land on your shoulder, eating out of your mouth, and cuddling. They do not seem to know how tiny they are, and may not be afraid of cats or dogs. Their personalities are the same as much larger parrots, so like small dogs they may try to attack other pets. On the other hand, if properly introduced they may befriend them.

The most commonly kept Parrotlet in the USA is by far the Celestial or Pacific Parrotlet. The Mexican Parrotlet, Spectacled Parrotlet, Green-Rumped Parrotlet and Yellow-faced Parrotlet are also fairly common pets. Their popularity as pets has grown due to their small size and large personalities. Parrotlets are commonly known as playful birds that enjoy chewing as much as their larger Amazon counterparts. Being highly intelligent and active parrots, parrotlets must have ample opportunities to play and exercise. Environmental enrichment must be made a part of their lives as to prevent boredom. Parrotlets keep themselves more than occupied when left alone for several hours, so long as they are provided with an array of chewable and destructible toys to play with. However, when their keepers get home, they often greet them with lovely chirps and whistles to let them know they want attention. They can mimic speech with a somewhat impressive vocabulary though their voice is very small. Males mimic better than females do. They can be very territorial inside their cages and may try to bite if a human reaches in, even to feed them. They consider the cage to be their sole territory. But the same bird, when outside his cage, can be very affectionate—flying over to land on your shoulder, eating out of your mouth, and cuddling. They do not seem to know how tiny they are, and may not be afraid of cats or dogs. Their personalities are the same as much larger parrots, so like small dogs they may try to attack other pets. On the other hand, if properly introduced they may befriend them.

Interaction & Social Behavior with other Birds (Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Caution must be advised regarding interaction with other birds. Very often a Parrotlet, especially a Pacific, will attack a much larger bird with no regard for their own small size. Particularly when they become mature enough to breed, they can become especially hostile toward other birds. This can pass in time. Normally they get aggressive in breeding season or during a first molt. Do not allow Parrotlets to be unsupervised around other birds. See my breeding section for keeping more than one pair of Parrotlets in the same room. Parrotlets, like their Amazon cousins, can be quite willful. It is important to socialize and train them the exact same way you would a larger parrot such as an Amazon. Teach the “step-up” command from the beginning and use it at all times. These feisty little birds are often quite willing to be handled by all family members as well as visitors. Generally, they are not one-person birds which make them ideal for a family atmosphere.

Caution must be advised regarding interaction with other birds. Very often a Parrotlet, especially a Pacific, will attack a much larger bird with no regard for their own small size. Particularly when they become mature enough to breed, they can become especially hostile toward other birds. This can pass in time. Normally they get aggressive in breeding season or during a first molt. Do not allow Parrotlets to be unsupervised around other birds. See my breeding section for keeping more than one pair of Parrotlets in the same room. Parrotlets, like their Amazon cousins, can be quite willful. It is important to socialize and train them the exact same way you would a larger parrot such as an Amazon. Teach the “step-up” command from the beginning and use it at all times. These feisty little birds are often quite willing to be handled by all family members as well as visitors. Generally, they are not one-person birds which make them ideal for a family atmosphere.

Sexing Parrotlets (Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

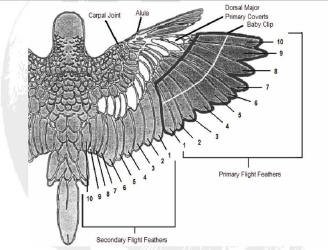

An important quality of Forpus Parrotlets is that they are sexually dimorphic. This means that the sex of the bird can be determined by visual observation which makes pairing birds easy and does not require surgical or genetic sexing. In all but one of the species within the Forpus genus, the males have a varying amount of vivid or deep blue on their rumps. The males of all species have shades of vivid blue on primary and secondary feathers on their wings. The females are similar in appearance but always lack the blue markings on the wings. Even young chicks can be sexed by their coloration, another bonus when deciding which offspring to hold back for future breeders. The only species in which the females have blue on the wing are the Yellow Face, and even then, the blue is of a much paler shade.

Origin (Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Parrotlets share much of the same regions with large parrots such as Macaws, Amazons, Conures, and Pionus. Their range spreads from the arid tropical zone of western Mexico, along the west coast just below Baja, California to the southernmost parts of Brazil and from the east to west coasts of South America. They inhabit Trinidad and have been introduced to the Netherlands Antilles and the West Indies. In the wild, Parrotlets feed on blossoms, seed heads, fruits and berries.

Parrotlets are very active and are always busy. Many Parrotlets happily enjoy playing on a small gym outside the cage. However, remember that they are very small and should be supervised at all times when out of the cage. They tend to like to hide behind cushions, which can have obviously dire results if the owner doesn’t know where they are at any given moment. If the bird is not on your shoulder or in its cage, keep your eye on it. I have had great success using my Birdie Playpens for Parrotlets. These allow the birds to play in a safe environment and are great for traveling and taking your new best friend places he normally would not be able to go.

Parrotlets are very active and are always busy. Many Parrotlets happily enjoy playing on a small gym outside the cage. However, remember that they are very small and should be supervised at all times when out of the cage. They tend to like to hide behind cushions, which can have obviously dire results if the owner doesn’t know where they are at any given moment. If the bird is not on your shoulder or in its cage, keep your eye on it. I have had great success using my Birdie Playpens for Parrotlets. These allow the birds to play in a safe environment and are great for traveling and taking your new best friend places he normally would not be able to go.

CAUTION: Watch out for ceiling fans – Many accidents are caused by owners not keeping the birds wings clipped or not making sure the fans are turned off when the bird is out of the cage. If the fan is not needed – I advise putting a piece of tape over the switch on the wall to remind and keep family members from turning on the fans.

Species: (Top↑) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

The information on this page is mainly for the Pacific Parrotlet.

Click on the links below for more info about the different species.

Forpus

The genus Forpus includes all the species of parrotlet commonly kept as pets. The following species within three genera are considered to be parrotlets.

Mexican Parrotlet (Forpus cyanopygius)

Green-rumped Parrotlet (Forpus passerinus)

Information, Care, Diet, Breeding

Blue-winged Parrotlet (Forpus xanthopterygius)

Turquoise-rumped Parrotlet (Forpus xanthopterygius spengeli)

Spectacled Parrotlet (Forpus conspicillatus)

Information, Care, Diet, Breeding

Dusky-billed Parrotlet (Forpus modestus) – or Sclater’s Parrotlet

Pacific Parrotlet (Forpus coelestis) – or Celestial Parrotlet

( You are on the Pacific Parrotlet Page already)

Yellow-faced Parrotlet (Forpus xanthops)

Information, Care, Diet, Breeding

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Diet & Harmful Foods:

For: Pacific Parrotlet and Green-rumped Parrotlets

LuckyFeathers: We feed each Parrotlet a high quality cockatiel seed mixed with low sunflower count. Also we mix in a high quality pellet food. I wean all of my babies onto Wild harvest Cockatiel Seed and Pretty bird pellets mixed into the seed. I wean my babies onto this formula because both products are available to my customers in any part of the USA. You can get the Wild Harvest mix at your local Walmart and the pretty bird pellets can be picked up at almost any pet shop. We also supply each baby with lots of millet for the first few months and recommend that my customers also supply millet every day for at least the first week after receiving your new baby. Parrotlets are recommended to have both seed and pellets as a daily diet. Sunflower seeds are a great source of vitamins and fatty acids that Parrotlets need. However you must watch your bird and make sure it is not eating the sunflower seeds only. Many parrots like the sunflower seeds so well that they eat nothing else. If you find that your Parrotlet is doing this, try to leave the seed in for a longer period of time before changing it. Many times this will cause the bird to eat the rest of the seed mix after it has picked out all of the sunflowers. We also use and recommend a liquid bird vitamin that can be added to the birds water. If you are feeding your Parrotlet pellets or a seed pellet mix, we do not recommend vitamins on a daily basis. The pellets are loaded with vitamins so only give your bird liquid vitamins once or twice a week. A diet with to much vitamin content can cause your Parrotlet to get ill or have health issues. Twice a week our birds get one of the below treat meals or some kind of fruit or veggie.

LuckyFeathers: We feed each Parrotlet a high quality cockatiel seed mixed with low sunflower count. Also we mix in a high quality pellet food. I wean all of my babies onto Wild harvest Cockatiel Seed and Pretty bird pellets mixed into the seed. I wean my babies onto this formula because both products are available to my customers in any part of the USA. You can get the Wild Harvest mix at your local Walmart and the pretty bird pellets can be picked up at almost any pet shop. We also supply each baby with lots of millet for the first few months and recommend that my customers also supply millet every day for at least the first week after receiving your new baby. Parrotlets are recommended to have both seed and pellets as a daily diet. Sunflower seeds are a great source of vitamins and fatty acids that Parrotlets need. However you must watch your bird and make sure it is not eating the sunflower seeds only. Many parrots like the sunflower seeds so well that they eat nothing else. If you find that your Parrotlet is doing this, try to leave the seed in for a longer period of time before changing it. Many times this will cause the bird to eat the rest of the seed mix after it has picked out all of the sunflowers. We also use and recommend a liquid bird vitamin that can be added to the birds water. If you are feeding your Parrotlet pellets or a seed pellet mix, we do not recommend vitamins on a daily basis. The pellets are loaded with vitamins so only give your bird liquid vitamins once or twice a week. A diet with to much vitamin content can cause your Parrotlet to get ill or have health issues. Twice a week our birds get one of the below treat meals or some kind of fruit or veggie.

Whole cereals and whole grains: spray millet, amaranth, barley, couscous, flax, whole-grain pastas, oat, quinoa (truly a fruit but used as a cereal), whole-wheat, wild rice, whole rices.

Edible flowers: My Parrotlet Seed Mix

carnations, chamomille, chives, dandelion, daylily, eucalyptus, fruit tree blossoms, herb blossoms, hibiscus, honeysuckle, impatiens, lilac, nasturtiums, pansies, passion flower (Passiflora), roses, sunflowers, tulips, violets.

Note: that the leaves of some of these plants are poisonous to parrots.

Greens and/or weeds: (Top)

mainly ; bok-choi, broccoli and/or cauliflower leaves, cabbage leaves, collard greens, dandelion leaves, kelp, mustard leaves, seaweeds, spirulina, water cress.

occasionally amaranth leaves, beet leaves, carambola (starfruit), chard, parsley, spinach & turnip leaves. All of these feature high oxalic acid contents that induces production of calcium oxalates (crystals/stones) by binding calcium and other trace minerals present in foods and goods with which they’re ingested, possibly leading to calcium deficiencies and/or Hypocalcemia in minor cases, liver or other internal organ damage or failure in more severe cases.

Fruit

(except avocados which are toxic): all apple varieties, banana, all berry varieties, all citrus varieties, grapes, kiwi, mango, melons, nectarine, papaya, peach, all pear varieties, plum, star-fruit. Pits and seeds from every citrus and drupe species must always be discarded as they are intoxicating. However, achenes and tiny seeds from pseudo and true berries (bananas, blueberries, elderberries, eggplants, persimmons, pomegranates, raspberries, strawberries, tomatoes) are all acceptable.

Legumes: almonds, beans, lentils, peas, nuts and tofu.

Grain and/or Legume sprouts: My Parrotlet Seed Mix

adzuki beans, alfalfa beans, buckwheat, lentils, mung beans, pinto beans, red kidney beans, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds. Caution with only lima bean and navy bean sprouts which are toxic. Red kidney beans must be thoroughly cooked, as uncooked red kidney beans are toxic.

Vegetables:

(except uncooked potatoes, uncooked onions and all mushrooms): beet, broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, cucumber, all cabbage varieties, fresh beans, fresh romane lettuce, fresh peas, parsnip, all pepper varieties, all squash varieties, sweet potatoes, tomato, turnip, yams, zucchini.

Pellets: (Top)

specifically formulated for small tropical Parrot species.

Other fat-free, healthy and nutritious human foods.

Adding these foods provides additional nutrients and can prevent obesity and lipomas, as can substituting millet, which is relatively low in fat, for higher-fat seed mixes. Adult parrotlets often do not always adapt readily to dietary additions, so care must be taken to introduce healthy diets as young as possible (ideally weaned onto fresh foods before introducing chicks onto seeds). Parrotlets like other Parrots learn mainly by mimicry and thus most adult parrotlets will be easily encouraged to try new foods by observing another bird eating the food, or by placing the new food on a mirror.

Parrot species (including Parrotlets) are herbivores. Consequently, they should be fed vegetarian diets that are ideally supplemented with vegetal proteins. Produced by the combination of any type of whole grain/cereal with any type of legume/pulse. Eggs (hard-boiled and/or scrambled) are the only appropriately healthy source of animal proteins. Mostly for birds in either breeding, growing, moulting and/or recovering conditions. High levels of proteins (most particularly animal proteins) is unhealthy for Parrotlets and any other Parrot species living under any alternate conditions (i.e. non-breeding, pets).

Harmful Foods: My Parrotlet Seed Mix

This is a short list of harmful foods for birds, obviously there are other items and you need to do your homework before you share any foods with your bird.

*Chocolate

*Apple Seeds

*Avocado or Guacamole

*Onions

*Alcohol

*Mushrooms

*Tomato Leaves

*Salt – Be careful with foods that have salt. My neighbor gave her Amazon a piece of pepperoni off of her pizza and the bird got ill and passed away the next day. She had an autopsy done and the vet told her the bird died from super high sodium levels, She claims that she did not regularly give her bird any human food and he only had one large piece of pepperoni the night before. Over the years I have heard other stories about birds getting very sick from to much salt.

*Caffeine (in any form)

*Dried Brown Beans (Fully Cooked Beans Are Safe)

*Any High Fat Food

Apple Cider Vinegar (Top)

I use Apple Cider Vinegar in my birds drinking water. I have done lots of research and read many different studies and articles written about the health benefits of ACV. Below I have listed just a couple links to more information for you.

PLEASE NOTE: HEATED vinegar emits toxic fumes similar to carbon dioxide. Bird owners have lost their pets by adding vinegar to their dishwashing cycle, or used it to clean coffee machines.

Parrotlets are very active, playful birds. They need a roomy cage to keep them busy. Because of their playful nature, it is best to get them a cage that is large enough for their acrobatics. A parakeet-sized cage might seem right for their size, but it is better to take a step up to a lovebird or cockatiel-sized cage. The cage should for an adult should be at least 23 X 12 X 16 and up. The bar spacing should be no larger than half an inch so the birds cannot get their small heads caught between the bars, and have horizontal bars. For an adult parrotlet I recommend the largest cage that you can afford. For a baby one year and younger I recommend starting out with a small parakeet size cage. As babies they will feel more secure and it will be easier for them to find the food and water. You can pick up a small starter cage for about $18 at Wal-Mart. They love a variety of interesting toys from which they can swing and hang, as well as mirrors and ladders. They need a stimulating environment so they don’t become bored. We suggest that you purchase lots of extra toys so they can rotate them weekly to keep their parrotlet amused. Because the love to chew, I always get the non-treated wood toys normally made out of pine. Parrotlets should be allowed to chew. It is an important part of being a real parrot.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Breeding Parrotlets: (Top↑) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Note: The below breeding information is valid for the pacific, Green-Rumped and Spectacled Parrotlets. Their may be some small differences between the three different kinds of Parrotlets, but as far as diet, breeding, nesting and handfeeding, I personally have not seen any difference and following the same practices with each has been very successful for me.

Parrotlets, particularly hens, should be at least a year old before they attempt to breed or they can become egg bound and die. Males who are too young often do not provide enough food for the hen and the babies which are then abandoned or destroyed. Young pairs can be kept with one another until they go through their first molt, then they should be separated until they are at least eleven months old. It is not uncommon to have hand-fed birds begin laying eggs as young as six months – which can be disastrous.

The male will usually investigate the box first and when he deems it safe, will try and entice the female into it. Once mating has taken place, the hen will lay from four to eight eggs although Pacific hens have been known to produce ten fertile eggs. She will hardly leave the nest box from several days prior to laying until the last baby is gone, which can be as long as nine or ten weeks!

Parrotlets do breed better when you have more than one pair as long as they can hear each other but not see each other. Many people trying to breed a single pair have not had success. This is very important! Stack the cages on top of each other or put something solid in between them so that they can not see each other. These birds cannot be within eye sight of another pair. Not following this suggestion can result in death. Males are very protective of their mates. If they see another male in the same area they will go into attack mode. A Parrotlet will kill its mate to keep it away from, or from flirting with others.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Parrotlet Breeding Season

Pacific & Green Rump Parrotlets do not have a programmed breeding season when kept inside. However, it is best for the health of the birds to limit the amount of clutches they have per year. Most breeders allow their Parrotlets to have two clutches, then rest for two to three months, then let them breed again. (Again good record keeping is a must!) This usually results in three or four clutches per year. I allow my birds to have 3 clutches per year. My Parrotlets normally take a break on their own after the second clutch. This break is normally about 3 months long, then they will breed again. If they do not take a break and go right into a 3rd clutch I will take the box off of the cage as soon as the babies from the 3rd clutch are pulled or I will move the breeders into a larger resting cage where they can get some flight exercise.

VIDEO – (opens in new window)

Caging

Most breeders have the best success with caging anywhere from 18″ square up to 48″ long and anything in between. We are currently using double breeder units with each side measuring 18″x18″x20″ with about 20 inches between units. If cages are placed too close together, the birds may spend all their time arguing and fighting with any neighbor they can see. A visual barrier must be placed between each cage to avoid potential problems. A Parrotlet will kill its mate to keep it away from, or from flirting with others.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Nest or Breeder Box *My Nest Box – For Sale Page

Parrotlets are not nest builders, they will generally accept just about anything provided for them. Breeding pairs should have nest boxes that are six inches wide by ten inches tall and seven inches deep, I currently use the standard budgie nesting box. Place untreated pine shavings in the bottom of the box. About 2 inches deep should be enough. They are not like finches so there is no need to have any nesting material in the cage as the hen will not normally “build” a nest. In most cases she will be taking out the pine shavings from the nest box and you will be replacing them. Go ahead and place it in the box for the hen. Boxes should be placed on the front of the cages when possible so that when the Parrotlets look out, they only see the inside of their cage. This will help them to feel more secure. Some parrotlets, particularly Green Rumps, are fond of throwing the nest material out of the box so be sure to keep it replaced. Babies can develop crippling orthopedic problems if left on the bare floor. Conversely, sometimes parrotlets will bury their eggs and lose them in the shavings. Start checking nest boxes daily so you will be able to monitor the pairs and deal with any problems as they arise. Also, following a routine will teach the parrotlets to tolerate your inspections and intrusions.

Toys, Perches & Swings

I keep a perch, swing and at least 1-2 toys in every breeding cage. I believe it is very important to have lots of toys available for breeding pairs. I will be discussing this in another section later.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Breeding Diet:

Nutritionally, it’s more of the same – more fat & more proteins. Follow the normal diet suggestions that I describe above. Except breeding birds will want a greater supply of soft foods such as eggs food, soft fruits and vegetables and millet as these will be the foods that they feed to their young. Supplying these from the start will reassure the breeders that there is an ample food supply to sustain potential chicks, making it more likely that they will breed. High protein foods such as eggs are also advisable at this time.

A calcium supplement is of vital importance at this time, as the hen will be depleting her calcium reserves in egg production. Calcium deficiency at this stage could easily lead to egg binding. Egg binding occurs when the hen’s body has insufficient calcium to deposit on the surface of an egg. The resulting egg is soft, and so when she contracts her muscles to press the egg out, it merely deforms and remains lodged within her. If not treated quickly, this condition can easily be fatal – the hen can succumb to exhaustion, or the egg can burst inside her. Cuttlebone is the obvious solution to this problem, although you can also get commercial calcium supplements designed to be added to water.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Pairing – The Bonding Process

The disposition of the Parrotlet carries over to breeding practices. Protect them from territorial fights by not putting adult pairs together or in close proximity. If in a double breeder cage, the divider must be solid, not wire. Although some have tried colony-breeding in large cages or flights, they can become very aggressive during breeding and have been known to kill even their own mates or chicks.

Parrotlets bond for life, however, I have split up and re-paired unproductive or problem pairs many times with good results. You must be careful and handle repairing very cautiously.

When setting up a new pair, the hen is placed in the breeding cage several days before the male so that she may become familiar with her new surroundings. Once the male is placed in the cage, watch them from a distance to make sure normal arguing and bickering does not escalate to serious injury. Be ready to step in immediately if you feel either bird is in danger. I suggest putting them next to each other with a cage or wire divider in between them for one to two weeks in advance. Then try putting them together. This process has worked for me many times. Once a male or female decides they do not like the other mate, it is almost always to late. At that point you will have a very hard time getting them to bond. In an attempt to avoid this from happening I always use the divider cage first. Once i see they are not fighting through the wire or have started to feed each other through the wires I generally go ahead and put them together and watch them closely.

Caution of Young Males ( 5 months to a year old )

During this time the male will start to sexually mature. He will be come over aggressive. this is not a good time to introduce him to a mate without close supervision. Also a young bonded pair may have problems during this time also. Even though they were put together when they were babies and have been together all this time – The male entering sexually maturity needs to be watched close so that he does not hurt or even kill the female.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Fighting Pairs

Never pair a much older male (over a year who has bred) with younger hen (under a year who has not bred). He can get frustrated if she doesn’t want to breed and starting picking on her.

Keep the wings clipped of the aggressor. This will keep your pairs calm.

If you ever see blood, IMMEDIATELY remove one of the mates from the nest. Males will peck and bite the female’s toes and legs to try to chase her into the nesting box, if she’s not ready to mate he may kill her. (The female can be the attacker also) After separating them, let them sit side by side in adjacent cages and see after a few days if they look like they are ready to be paired again. I give them a second chance, after this I repair with a new mate.

Mating

When parrotlets mate the male will tend to put one foot on the females back and then they will turn their tails over so the cloaca’s touch, sometimes the female will put her foot on the male. It is very (VERY) important that you have secure perches that are not loose at all in anyway. If you have loose perches you may get unfertile eggs over and over. It is also normal for parrotlets to mate at the bottom of the cage or in the nest box. Some pairs will mate every day right up until the hen lays the first egg. Normally it take only 10 days from a successful mating for the first egg to be laid. The female may not start sitting on the eggs until she has laid 2 or 3. At normal room temperatures of 76 – 80 degrees it is possible for a fertile egg to be 10 days old before the female starts to sit.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Breeding Season

There is no defined breeding season for Parrotlets kept indoors. My birds breed in every month of the year. Although there are two windows in my current indoor birdroom the spectrum rays do not pass through the glass, I use full spectrum lighting. The lights come on at 8am and go off at 11pm. The birdroom is climate controlled with AC and heat. I never let the temperature go below 80 in the summer. In the winter months it is hard to keep the temperature at 80 all the time, so I have an average temperature of 75 in the winter months.

Laying Eggs

Once a hen begins laying, she can be expected to lay one egg every other day, up to 4-6 eggs, although any amount up to about 10 is possible. If three days pass without laying, it is safe to assume the clutch is complete.

I do have some hens who skip a day and lay the eggs every 2 days.

Hatching

The eggs take 21 days to hatch (more like 24 in the larger species), although this can be increased for the first egg if the hen doesn’t start brooding immediately and potentially decreased for later eggs in the clutch for the opposite reason.

Since the eggs are laid two days apart and a hen usually starts sitting tightly from the first or second egg, you can expect a wide spread in the ages of the chicks. This shouldn’t be a problem except in the cases of particularly large clutches. I personally only allow my hens to have 3 or 4 babies at the most. Once the 4th baby is hatched or starts to hatch I remove the baby that hatched first. By this time the first baby hatched is going to already be about 10 to 12 days old. This allows the rest of the eggs room to hatch and helps keep the female from wearing herself out with so many babies. If you do not remove babies as I do after the 4th hatch, you take the risk of any eggs after the 4th one not hatching. This is because the female no longer has the room she needs to keep the eggs warm and also with 3 or 4 babies continually moving the eggs around in the box many of them crack. You will have a much higher yield if you remove some of the babies. If your hen has only laid 3 or 4 eggs you will not need to worry about this.

Foster Parents

Pacific Parrotlets are excellent breeders and highly dedicated parents. They are commonly used as foster parents to incubate eggs and raise the chicks of other parrotlet species as well as their own species. I have several pair that for whatever the reason they just will not sit on the eggs. I remove the eggs from the box and place them under a different hen. Anytime you have to foster chicks or eggs make sure to mark the eggs and keep a close eye out for the hatch date. Keep good records and use a safe food coloring to make the babies on the feet or the back. This will allow you to keep track of who the foster chicks are and their bloodlines.

Tips For Breeding Parrotlets (Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Bird Talk Magazine, August 2002

Breeding parrotlets is not for beginners. Parrotlets are aggressive and can be challenging to breed unless you become educated on their needs.

1. Parrotlets breed best when you have more than one pair, and they can hear but not see one another. Set up barriers between the cages.

2. Parrotlets breed best in cages that are at least 24 by 24 inches. Yellow-faced parrotlets need bigger cages at least 24 by 36 inches. Nest boxes should be small, grandfather-type boxes at least 10 inches tall, 7 inches wide and 7 inches deep. I use a 2-inch nest hole with a small perch underneath and fill the box up to a couple of inches to the hole with clean pine shavings.

3. Parrotlets do not build nests but chew and move shavings around, so make sure they have a lot even if it must be replaced from time to time. Place the box on the outside front of the cage in the highest corner possible. This way, the parrotlet will only see the inside of the cage when it looks out of the nestbox and feel more secure.

4. In the wild, parrotlets nest in tree cavities. They also prefer fence posts, if available. Several biologists have had success with the birds nesting in man-made boxes even when tree nest cavities are available.

5. Breeding pairs of parrotlets need more food and better variety than pet parrotlets. Include some seed in the diet of breeders. This increases fertility and helps prevent stress bars in the offspring. Give them a mix higher in fat and protein, such as safflower-based hookbill mix with sunflower and hemp.

6. They also need fruit, vegetables, greens, whole-grain breads, cooked dried beans, rice and pasta. Higher protein foods such as egg food, tofu and cooked lean chicken should also be added. Sprouted seeds are also excellent. Cuttlebone and mineral block is a must, as is powdered calcium and vitamins sprinkled on the fresh foods several times a week. Calcium is extremely important to prevent egg binding in females, so supply as much cuttlebone as the females will eat. Many hens will eat a 6-inch cuttlebone a week for several weeks prior to laying.

7. Most parrotlet species do not have a programmed breeding season. However, it is best for the health of the birds to limit the amount of clutches they have per year. Most breeders allow their Parrotlets to have two clutches, then rest for two to three months, then let them breed again. This usually results in three or four clutches per year. Parrotlets lay a white egg every other day until a clutch of 6 to 8 is reached; some hens will lay as many as 10 but 6 to 8 eggs is average.

8. Incubation is 21 days. Chicks hatch in the order they were laid. Most breeders pull them for hand-feeding at 10 – 14 days. I try to pull mine around this time right before the eyes open. I like to be the first thing my babies see in life.

9. Parrotlets should be fed every four hours but not during the night. They start picking at food at 4 to 5 weeks and are usually weaned by 6 or 7, unless they are spectacled parrotlets, which usually take 8 or 9 weeks. It is always best to keep babies an extra week after they are weaned just incase one of them reverts back to formula for a few days. This does happen often.

10. Parrotlets do not bond with the hand-feeder, but rather they bond with the person who they spend the most time with after they are weaned.

11. Most species are mature at one year of age. In the wild these birds are sometimes breeding as early as 5 or 6 months of age. However it is not recommended for bird breeders to allow any parrotlet to breed prior to one year. (Top)

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

I recommend a video so you can see exactly how to feed the chick as just one mistake when feeding can drown the chick. Do some research on YouTube and the internet and watch some videos if you do not know what you are doing. One of the best ways to learn is to find someone who is already rearing baby parrots and try and visit them to see how they do it. Be warned, it seems very easy when you see an experienced hand feeder at work but there are so many things that can go wrong and with these very small chicks, you do not normally get a second chance – one mistake and they are dead. Parrotlets start to wean around 5 weeks of age and great patience is needed at this time, at this time food should be offered on a flat low dish on the cage floor and lots of variety.

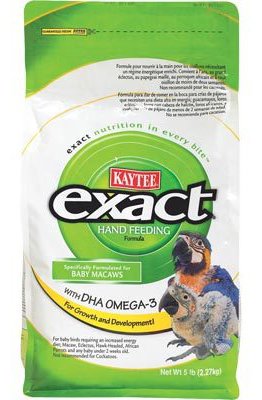

Exact Handfeeding Formula

I use Exact Handfeeding Formula and have had great success with it over the years.

I use Exact Handfeeding Formula and have had great success with it over the years.

Exact Hand Feeding Formula was the first “instant “ formula available and is the most researched and respected product used by professional breeders, veterinarians and conservation programs throughout the world. All of my breeder friends also use this formula.

Exact’s balanced, high-nutrient formula helps babies grow faster, wean earlier and develop better, brighter plumage.

When used properly, exact will not cause crop slow-down

exact Hand Feeding Formula contains probiotics to encourage a healthy population of intestinal microorganisms. The selected species have been chosen specifically for their vitality, stability, and overall benefits to a bird’s system.

Digestive enzymes (amylase and protease) are included to insure adequate digestion of carbohydrates and proteins. These enzymes are of particular value in the newly hatched baby or in a bird experiencing digestive difficulties.

exact Hand Feeding Formula has compatible tastes and ingredients with exact Conversion and exact adult daily diets reducing digestive upsets during weaning, or when pulling young from the nest of exact fed parents.

With DHA, an Omega-3 fatty acid for development of heart, brain, and visual functions

High-Nutrient Formuladeveloped for the needs of Baby Birds

Babies develop better feathering & brighter plumage

Trusted by Avian Veterinarians & Breeders

Babies grow faster & wean earlier

SPECIAL NOTES FOR PREPARATION (Top)

•IMPORTANT – DO NOT REUSE MIXED FORMULA!! Discard and mix fresh at each feeding.

•For hatch to 2 days old – formula should be made in small quantities and thoroughly stirred before feeding. Separation at this concentration is expected and is not a problem at this early stage because primary requirements are for water and water soluble nutrients. After chick is two days old, the food concentration must be increased (see feeding chart).

•Microwaving should be avoided. Microwaving can create “hot spots” in the formula and increase the likelihood of accidental crop burns. If required, limit microwaving (on high) to no more than 5 seconds per ½ cup of mixed formula at a time. Be sure to follow this with vigorous stirring before retesting the temperature and feeding. Cover large batches of formula while microwaving to avoid a moisture loss. STIR FORMULA THOROUGHLY TO AVOID POTENTIAL OF BURNING THE CROP. Always test formula for proper temperature before feeding.

MONITORING A HAND FED BABY BIRD

•Monitoring weight gain and loss is the best way to identify a problem before it becomes visibly obvious. Weigh and record the weight of each baby bird every morning before the first feeding.

•A healthy chick should gain weight every day until it begins the weaning process. If weight gain stops, but weight is maintained, watch the bird closely. Loss of weight indicates a problem and should be investigated immediately.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Syringe Feeding

Syringes are widely used for handfeeding. It also benefits from the chick’s natural feeding response and teaches the baby to eat. The handfeeder can easily control the flow of the formula. I prefer the syringes with the rubber-tipped plungers, as they operate very smoothly.

However, it is more difficult to know when the mouth is full. Another potential problem is that syringes are very difficult to disinfect. I keep mine soaking in disinfect solution at all times when not in use. I rinse them off good before using.

I keep the syringes very clean and have not had a problem with bacterial infections.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Spoon Feeding

Spoon feeding is the easiest and “fool-proof” way to feed babies. It takes advantage of the baby’s natural feeding response and introduced it to the taste of food. You can do a search on Yahoo to see videos of how this is done.

The size of the chick will dictate the size of the spoon. I have a couple of small spoons that I like. I bent the sides up to form a trough. This allows me to control the flow of the formula quite easily. I watch carefully to see if the baby’s mouth is full, or if it needs to take a breath.

The negative part about spoon feeding is that it gets very messy. Have some wet paper towel available for a clean-up after the feeding.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Dixie Cup

Some breeders swear by this method. They use a Dixie cup with one edge pinched to a point. I personally have never used this method, but it sounds easy and the big benefit is that there are no dishes to wash afterwards.

Power Feeding /Force Feeding / Gavage / Tube Feeding

I do not power feed my babies. I have had to tube feed over the years when the baby simply will not take the formula any other way. Power feeding is also known as Force-feeding, gavage or tube feeding. Gavage feeding is a method of feeding, in which the food is pumped into the crop through a tube that has been put down the esophagus and into the crop.

Gavage feeding is typically used by handfeeders with too many babies to feed. Birds fed in this manner never learn to eat and can be very difficult to wean.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Full Spectrum Lighting ( Very Important )

I use full spectrum lights only in my birdroom.

Glass windows filter out up to 90% of the beneficial UV spectrum unless that glass was made pre 1939. Aluminum screening used can filter out 30% or more UV light. High-grade acrylic (cages) filters out less than 5% of the UV light.

Sunlight and artificial sources of light are measured by color temperature and rendering. If you were to consider the intensity of the sun at noon daylight, it is about 5500 degrees Kelvin (K).

Natural light not only provides warmth, but brings out the intensity of colors in a way that artificial fluorescent lighting rarely mimics.

Natural daylight is also measured at a color rendering index (CRI) of 100, which shows the vibrant and intensity of colors in and around our environment. Our full spectrum light for birds, the Vital Lamp spiral bulbs, have a CRI of 88, and will bring out colors in your bird’s feathers that you may not have even known existed while using a standard fluorescent cage light.

Full spectrum fluorescent light emits light in all parts of the visual spectrum and some in the ultraviolet range (short-wavelength, high-energy light). To be a full spectrum bulb, the color temperature must be 5000K or greater, and the CRI must be at least 88

A standard fluorescent bulb generally only has a CRI of between 60 and 75, which means the intensity of the source of light is much lower, the temperature is cooler, and there is a noticeable difference or dulling of colors when objects are placed under a standard bulb.

Some Major Benefits of full spectrum lights

* Prepares bird for seasonal changes

* Encourages breeding behaviors

* Strengthens immune system

* Lowers obsessive/compulsive behavior frequencies

* Relieves psychological distress

* Mimics a bird’s natural environment

* Aids in Vitamin D Synthesis

* Maintains constant environmental temperature

* Aids a bird’s visual acuity

* Increases the longevity of the captive bird

Birds have four-color vision and the lower wavelength ultraviolet (UVA) adds the fourth visual perspective. Correct spectrum and photo period of light are also critical factors in normal preening and Breeding as well as the skin and feather health of birds. If a bird’s system is not stimulated through adequate environmental lighting to maintain proper endocrine function, it may become lethargic and not continue normal preening or breeding behaviors.

One of the greatest benefits of full spectrum light for birds is the natural synthesis of Vitamin D precursors allowing the animal to naturally regulate calcium uptake.

Another important benefit of full spectrum lighting is the effect it has on the glandular system; the Thyroid Gland controls how and when the other glands function and for it to function properly, it needs to be stimulated by normal photo periods of full-spectrum light. The Hypothalamus is involved in proper feather development and skin. The Pineal Gland controls the cyclical processes such as molting and the reproductive cycle.

(Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

full spectrum light for birds can help reestablish the body’s natural rhythm, which controls things like timing of sleep, hormone production, body temperature, and other biological functions.

What characteristics should the light have? (Top)

What Kind of Light do I get?

There is a lot of conflicting information about what kind of full spectrum lighting is best for birds. But it seems to be generally agreed that the following is ideal:

It should have a CRI (color rendering index) of 90 or more, preferably 95-98. Natural sunlight has a CRI of 100.

A color temperature of 5000K is considered to be perfect but temperatures up to 5500 or so are OK. 5500K is the color temperature of the sun at noon on the equator.

The light fixture should have an electronic ballast, not magnetic, to avoid flicker problems which are invisible to humans but stressful to birds. Fluorescent light fixtures are currently manufactured with electronic ballasts because they are much more energy efficient than the old magnetic ballasts. But this changeover is fairly recent (beginning around 2002) and older fixtures might have a magnetic ballast.

What I Use: (Top) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

I use a CRI of 90 and Color temperature of 5500K.

But some lights that call themselves full spectrum are only talking about the human visual spectrum, which is more limited than the avian visual spectrum. You need to know that you can NOT get the bulbs you need at walmart or kmart. They need to be ordered. I will be offering these bulbs on my website. If you want to use FS Lighting, contact me directly and I will tell you who I order my bulbs from.

Teaching Parrotlets To Talk (Top)

Parrotlets are one of the most intelligent birds that we have ever known. They easily & quickly master understanding of the human language and learn the names of certain thing almost instantly. They are creative and ingenious.

Often, birds start out being “closet talkers”, meaning they will only talk if you are not in the room or if they are in their cages. They practice quietly and often you can’t quite figure out what they are doing. It starts out being a medley of sounds that eventually turn into distinct words. At first, it can have a squeaky sort of honk sound. When perfected, it retains a robotic quality. Many start out with a “song” rather than recognizable speech.

Holding your bird very close to your mouth while talking seems to encourage them to mimic you. Young birds have an instinctive ability to mimic the calls of their parents and learn the sounds of their flock. Imitating their sounds can encourage them to mimic yours. This is not easy for us, it can’t be expected for it to be easy for them.

Rather than teaching individual words, we use short phrases. Associating a phrase with an action teaches more than simple speech, it helps with training. Examples would be saying “Time for nite-nite” as you cover the cage. If said every evening, your bird will associate these words and actions with a bedtime routine. Even if he never learns the words, he will quickly learn that this means his day is at an end. If you have raised children, you are aware that they respond to short, familiar phrases. They like a lot of enthusiasm. So do birds. (This is why so many birds learn to repeat expletives – they are said with such enthusiasm.)

Both male and female Parrotlets can learn to talk. Many learn to speak at six months of age and some even sooner as early as 3 months, though at first it may be awhile before their persons are aware of what is being said.

The Parrotlet Biting State: (Top)

This section is for the single Parrotlet that was handfed as a baby and was very tame, and now all of the sudden is starting to bite you. If this does not describe your bird then the answer below will not apply.

The Question: Why does my Parrotlet bite me, why is it not tame anymore and what can I do?

The Answer: both male and females

This is such a hard question to answer because like people each Parrotlet has its very own personality and you can not treat each one of them the same way. There is no simple answer to the biting question, so I have put together a page that if read totally will give you an understanding of the answer and maybe even the solution. Parrotlets that are handfed as babies are generally not scared of anything. This of course depends greatly on the personality of each bird, but from my experience a handfed baby that grows up around people will not be scared of much. This can be dangerous for the bird. They have the personality of a large Amazon Parrot and because they are so small they are not aware of the dangers that come with this strong-headed personality. Please keep an eye out for dangers, it is your responsibility to keep the Parrotlet safe and away from other animals that may cause harm. The Parrotlet generally shows you that he is not scared when he is in his cage and feels secure. You may notice that he goes into attack mode when a stranger comes close to the cage or another bird is close by or even a strange dog or cat is in the room.

The biting stage normally starts between 6 months to a year old. Parrotlets love people too much. The biting does not mean that the parrotlet does not love you anymore. He/she loves you so much he/she has chosen you for his/her mate. The parrotlet becomes frustrated that it cannot drive you to the nest and the two of you are not setting up housekeeping. The parrotlet will bite you to drive you away from a potential suitor (your human mate, child, acquaintance or other pet). The Parrotlet is trying to drive you to the safety of his or her nest. He may bite other people to communicate that you already have a partner. The bird may become territorial when you hold him/her and bite any one that intrudes your space. Although these bites can be extremely painful, they are in fact love bites and almost never will they break the skin.

Limits must be set early. The male parrotlet or aggressive female parrotlet in this biting stage, does not belong on your shoulder. Hold the bird on your finger at low chest or waist level. I believe that Parrotlets should also be stick or perch trained as well as hand trained so you can always handle them even when they are in the biting stage. Do not engage in rough play with the bird as that will bring out its natural aggression. Discourage nibbling on your body, or fingers. A jiggle of your finger and a firm “No” is all that you need for young Parrotlets. You must be consistent with this for it to work. At this stage do not give up on the bird. Please continue to hold and play with it during this stage process even if it is biting you. Start using a perch in place of your finger to hold him or her. If you stop working with the bird at this point it will revert back to being un-tame. This would be the worst mistake a bird owner could make. Remember that these little guys can live 15 to 30 years and how un-happy of a life it would have if it became un-tame and could no longer be held, pet or loved because it had lost its tameness. This is a natural stage for the parrotlet and it will only last about 8 to 12 weeks. Your parrotlet may come into this same biting stage each year as it matures and enters breeding season.

The Stages: (Top)

As a general rule each Parrotlet goes through different stages and at least one biting stage each year. The first stage starts as soon as the baby is pulled from the nest box.

Stage #1

The baby will not eat after being pulled away from his parents. This stage only lasts about 3 days. The breeder must be experienced and know how to force the baby to eat at this stage. After a day or two the baby will take the food with no fight.

Stage #2

The baby knows that you are the mommy, He no longer fights you to feed, he runs to you when he sees you and demands that you feed him

Stage #3

The baby is around 6 weeks old. He is hungry but not starving because you have started to give him seed mix. He is curious to explore the world and it is hard to get him to eat. At this stage you will feel that you are back to stage #1 and you will have to be firm and force the baby

( without hurting him ) to take the food. At this stage it is very important for the baby to eat the formula even if you notice him eating the seed mix. The reason is because he needs water and the nutrition from the formula until he is totally on a seed diet around 8 weeks of age.

Stage #4

The baby is very loving and tame, however it was just purchased by its new owner and arrived at his new home for the first time. Now the baby is going to be scared and stressed for a few days up to a week. It is important at this time to not force the baby to play or be held. Let him get used to his new home. Let him learn where is food and water are kept. Remember he has only knew one person in his life up to this point. It will take him a few days to get used to everything. After 3 days to a week you should then start taking him out, holding him and playing with him.

Stage #5

The baby is secure in his new home. He is now reaching the age of about 6 months and starting to mature. This age can also come late and is not always marked at the 6 month period. Some babies do not reach this mature age that we are talking about here until they are 10 to 12 months old. However in most cases it will come around the 6 month area. At this point the bird will start to see you as his mate. It is very important to follow the steps that I talked about above. If he continues to bite you and if it hurts – start using a perch to hold him on. Also this is a good stage to use the birdie play pens that I talk about on this page.

(Top of Page) (My Parrotlets for Sale)

Parrotlet Egg Laying / also see Egg Incubation

A Parrotlet hen will appear swollen in the vent area before eggs are laid. Another indication of impending egg laying is extremely large droppings. The average clutch will usually be four to seven eggs, although I’ve heard of up to 10 eggs being laid. The eggs will be laid every other day until the clutch is completed. The hen will not always sit tight until the second or third egg is laid. It’s not unusual to see several clutches of clear eggs before fertile eggs are produced. A pair may go through several cycles before actually producing chicks.

Broken/Missing Eggs

Some inexperienced young pairs may destroy their eggs or chicks. If a squabble has taken place in the nest box and an egg has broken, the hen may eat the broken egg in an attempt to keep the nest box clean. If the eggs are being deliberately destroyed, replace the newly laid egg with a plastic egg. I bought mine on eBay for about $4 for 6 of them. Once the birds realize the eggs can’t be destroyed, the problem is usually solved. It is not uncommon for this to occur to young, inexperienced pairs. Often the problem will resolve itself and the next clutch will go smoothly. However if they are tossing the eggs out of the box that can be another problem. Sometimes the plastic eggs will also solve this issue. Another way to sold this is to blow out the eggs by poking a hole in each end of the egg and then blowing the yoke out. After you blow out the eggs fill them back up with Tabasco hot sauce and then add a drop of glue on each end of the egg to cover the holes. Once the parents get a taste of the hot sauce they normally stop eating , cracking or tossing the eggs out. The next clutch should go smoothly for you.

Multiple Clutches

Although most pairs will rest between clutches, a very determined pair will continue to lay clutch after clutch. It is these pairs that must have their nestboxes removed for a forced “vacation.” A very determined pair will even attempt to nest in a food dish or on the wire grate of the cage. When this happens, the pair is moved to a different cage with new neighbors and an entirely different view. This generally results in breaking the breeding cycle.

Egg Incubation (Top of Page) (Parrotlet Babies for Sale)

The incubation period for most Parrotlets is 18 to 19 days.

Some hens will sit tight after laying the first egg. In a large clutch this can cause a vast age difference between the oldest and youngest chicks. The incubation period for most Parrotlets is 18 to 19 days. The hen will spend all of her time in the nestbox coming out only to defecate. The male will feed her either in the nest box or at the entrance hole. Sometimes a male will even help incubate the eggs, although it is uncommon. If several eggs have been laid before the hen begins incubating, it is possible for several chicks to be hatched on the same day.

Parrot Egg Incubation written by – Howard Voren ( also applies to Parrotlets – all Parrots )

During the many years that I traveled through the jungles of Central and South America, there was never an egg under incubation back home on the farm. We at Voren’s Aviaries never “counted our chickens” before they hatched. Due to the fact that I was near a jungle somewhere in the world about half the time, there was never anyone to tackle the responsibility who wasn’t already overburdened by my absence. As my collection grew near my goals and I began to curtail my travels, I became very involved with incubation.

Well over 8,000 psittacine eggs have passed through my various incubation procedures during the last four years. The numbers of birds that we have hatched successfully staggers most people (over 1,500 this year alone). I myself am more staggered by those that don’t hatch. Infertility can be depressing, but what really hurts are the babies that die in the shell sometime after the second week of incubation.

Due to my success as an aviculturist, I am called on by many professional breeders for advice. Being in this position allows me to see that everyone who incubates large quantities of eggs has similar problems. Although it is impossible to help people solve problems that I have not been able to solve myself, this communication allows me to question them freely and stockpile facts–facts that at some point lead to answers.

The first fact that becomes glaringly apparent is that the first 10 days to two weeks of incubation is the critical period. Correct procedures during this initial time will almost always result in a successful hatch.

Without exception, anyone incubating a reasonable quantity of eggs who claims a success rate of over 85 percent is not pulling the eggs as they are laid. They are either allowing the hen to keep the eggs until the entire clutch is laid, or they are leaving them with her for two weeks of natural incubation. Those who allow the hen to sit for two weeks have success rates well into the 90-percent range. Once this critical two-week period is over, the egg can be successfully brought to term with a wide variety of temperatures and humidities.

Temperature (Top of Page)

Under natural conditions, the most important factor in successful incubation is heat. As long as the egg gets enough of it and is not permitted to lose too much of it for too long a time, everything will be fine. This is true even though the actual temperature of the egg fluctuates drastically when the hen is off the nest. Hens that “sit tight” (those that rarely leave the nest) do not have a noticeably higher hatch rate than those that leave the nest at regular intervals. From this, it’s safe to assume that eggs have evolved to be less sensitive to temperature drops than to other more unnatural circumstances.

One thing that a bird cannot do no matter how hard it may try is overheat an egg. This, of course, is possible in an incubator. Overheating is one of the things that an egg is very sensitive to and can result in eventual death. Temperatures that have been used successfully range from 98.7 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit. At Voren’s aviaries, we have settled on 99.3 degrees Fahrenheit.

Of course, the best temperature for you to use will depend on many different factors. The most important of these factors is humidity.

Humidity (Top of Page)

It has been long assumed that 50-percent humidity is required for successful hatching. This is not necessarily the case. Humidities ranging between 38 and 52 percent have been used by different professionals under different circumstances. All have proven successful in the situations used. An egg should undergo a specific percentage of weight loss during the incubation period. This weight loss is achieved by the evaporation of water through the pores of the shell.

Since increasing the incubation temperature can shorten the time period in which it takes a chick to hatch, there is less time for the required water loss to take place. If using these higher temperatures, the lower humidities should be used to allow sufficient water loss during the shortened time period. Conversely, if lower temperatures are used, the chick will take longer to hatch, and higher humidities should be used in order to keep too much evaporation from taking place.

I have experimented with different humidities and found that under the same environmental circumstances, large eggs do better at lower humidities (38 to 45 percent), and smaller eggs do better at the higher range (46 to 52 percent). In fact, it is now standard procedure for me to incubate all macaw and Amazon eggs at between 38 and 42 percent humidity. Conure eggs at these humidity levels experience too much water loss and die, or hatch in a dehydrated state. For conures, we use a humidity level of 48 to 52 percent. I believe this is a function of eggshell calcification differences rather than a difference in the amount of water held in large eggs versus small eggs. In my aviaries, the larger birds generally produce eggs that are harder and thicker-shelled than the conures’. Logic tells one that an egg with a thicker and denser shell would require a lower humidity level in order to incur the same water loss as a thinner or less dense-shelled egg.

Differences in diets and individual metabolisms are the major reasons that there are so many different reports as to the ideal humidity to use in a specific case. One must not lose sight of the fact that a bird can sit on an egg under almost any reasonable humidity and hatch it regardless of how marginally over or under calcified it might be. This tells me there are major flaws in our basic incubation philosophies.

Turning (Top of Page)

The next most important aspect of incubation is turning the eggs. The number of times per day that a parrot egg should be turned in the incubator is still a subject of debate. Poultry research supports the theory that eggs should be turned between 12 and 24 times a day. However, some people, myself included, think that between four and eight times per day is sufficient.

Under my incubation conditions, I noticed a marked difference in development when the incubator was set to turn the eggs only six times a day instead of 12 times. The eggs developed more evenly. That is to say that the veins that grow out from the embryo covered a larger area and reached around to the “underside” of the egg much earlier in the incubation process than those turned every two hours. There was no difference in incubation time, but hatchability was increased.

Vibration (Top of Page)

Vibration is probably the most unconsidered variable that is responsible for mortality in the shell. It also explains why under “exactly” the same conditions, two different people can have completely different results using the same model incubator.

Minor differences in mounting positions, as well as the age and type of fan motors used, can have a great effect on the amount of vibration that is transferred from your incubator to your eggs. Eggs in their natural state are incubated in a vibration-free environment. It stands to reason that even the slightest bit of vibration can affect the development of those tiny veins in a negative way. The question is, how much can they stand before vibration proves lethal?

Hatching (Top of Page)

The first sign that hatching is around the corner is when you see the egg “draw down.” This is when the air space in the egg enlarges. It will change from its normal round appearance to elliptical. One side of this now-elliptical air cell will extend down one side of the inside of the shell. The other side remains up near the top of the egg where it has always been–hence, the elliptical appearance. At this point, many aviculturists move the eggs into a hatcher. Others prefer to wait until the first “pip mark” appears on the egg.

The “hatcher” is an incubator with high humidity and no turning mechanism. The high humidity is to make it easier for the chick to hatch. Since the incubation process is complete, the high humidity (the higher the better) does not interfere with evaporation but does make it less likely for the internal membrane to stick to the hatching chick. Chicks that get stuck to the membrane must be assisted out of the shell, or they will die trying to get out. Normal time lapse between major draw down and hatching is usually about three days.

Hatch Assistance (Top of Page)

Knowing when to enter into an egg and when to stay out is an art in itself. Many chicks have been saved by timely assistance, but anyone attempting this must remember that it is always a gamble. Hatch assist is something that you can consider if you have a chick that has come to term but for some reason does not hatch.

One should wait at least for an internal pip before even beginning to monitor an egg for possible need of assistance. An internal pip is when you can see the chick moving in the area of the air cell. This happens just prior to the chick attempting to break through the shell wall. Once broken through, the pip mark is called an external pip. If an external pip is not forthcoming, then there may be a need for assistance.

You also may have a problem if a chick externally pips one pip and then stops. Stopping to rest after the first pip is normal. If, however, two days pass and no further attempt has been made to continue the hatching process (more pip marks), then help might be necessary. With either of these two problems (just internal pip or just one external pip), you would proceed in the same manner.

Chip a small hole in the shell so you can see inside. There are some dental tools that are perfect for this work. You should make the hole where the pip mark is or where the pip mark should be. To determine where a pip mark should ideally be, estimate about 3/4 the distance down from the center of the top of the egg (the fat end) to where the expanded air cell ends along the side of the egg. If there is no pip mark, you will have to make a tiny hole. A small nail spun between the thumb and forefinger makes a perfect drill for this procedure.

Once you have drilled a hole or located the pre-existing pip mark, begin to chip away tiny pieces of shell until you can see what is going on inside. Sometimes a chick will pip and get stuck to an overly dry internal membrane. If this happens, the chick will not be able to rotate and pip in enough spots to facilitate hatching. A sure sign of this problem is when you notice upon candling that there are no veins left on the inside of the shell. The feet appear to be moving freely, and the chick keeps pipping at the same spot. In the case of no pip mark other than internal, the problem could still be an overly dry membrane. It might also be a problem of the head being poorly positioned and unable to make an effective strike on the shell.

Remember to keep the hole as small as possible. The membrane will usually be white in appearance. Paint the membrane with water using a tiny paint brush. This will make the membrane transparent and clearly show any veins that might still be carrying blood.

If the chick has not come through the membrane and you are convinced that it is overdue, then make a tear in the membrane to free the chick’s beak and nostrils. Be careful not to break any blood vessels in the membrane. Only work in spots that are free of vessels. This allows the chick to breath and eliminates suffocation as a possible cause of death.

You should now cover all but the smallest air hole with a small piece of tape. At this point, you have the choice of allowing nature to take its course or going in to complete hatching if you feel that there are no more live veins in the membrane, and the yolk has been completely absorbed. If the hole allows you to see that the membrane is completely devoid of veins and the chick has internally pipped and its only obstacle is a dry membrane, you might wish to take off the top of the shell and let the chick lift its head out of the torn membrane. When removing the shell and membrane from around the head, work from the nares back to the crown, if there are any hidden blood vessels they’ll be in the area of the crown. If no viable vessels are noticed as you proceed, then lift the shell and membrane off the bird’s crown down to the upper neck. If the chick is ready to come out, you will get what I call the “jack in the box” effect; that is, the chick’s head will pop straight up out of the fetal position. If the chick does not pop its head up and tries to return to the fetal position, even if you coax the head upward, it’s best to tape the bird in with paper tape (I use Micropore by 3M with great success) and try again in six hours. If the bird does pop its head up, at that point you can look down to see if there is any yolk that has not been absorbed. If none exists, the chick on the half shell should be placed in a small tissue basket back into the hatcher so it can crawl out when it is ready. This is when the last few veins at the navel have dried.

Pulling a chick out of the half shell too early can cause it to bleed to death. If, however, you can see some yolk sac, you should place the chick’s head back into the “fetal” position, place the top of the shell back on the egg, and tape it together. Place the egg back into the hatcher to allow the chick to finish absorbing the yolk. A chick in this situation will have to be released from the shell at the proper time.

Remember, always proceed with great caution. Good luck, and may all your eggs be fertile.

written by – Howard Voren

Howard Voren is a Psittacultural Scientist specializing in the maintenance and reproduction of Central & South American Psittacine birds. Information about Howard Voren can be found on his website at .

(Top of Page) (Hand fed Parrotlet Babies for Sale)

Health – Diseases – Illness (Top)

Note: Please also visit my Links page for information on many different bird health issues, diseases and illness.

Click Here

Many birds tend to become ill in case they are exposed to draught or quick changes in temperature. A bird who suffers from a cold fluffs up the plumage, behaves apathetic, and in case the animal caught a cold , the nose may also be running and from time to time the bird may sneeze. Other kinds of infections affect the lower respiratory tract (lungs, air sacs) and the bird makes sounds that remind of coughing. In fact, coughing is not quite correct since birds are unable to do so. They don’t have a diaphragm and due to this difference in anatomy they can just make sounds that are a bit similar to coughing. On the left you can see a bird whose nose is severely infected, (a bacterial infection).

Many birds tend to become ill in case they are exposed to draught or quick changes in temperature. A bird who suffers from a cold fluffs up the plumage, behaves apathetic, and in case the animal caught a cold , the nose may also be running and from time to time the bird may sneeze. Other kinds of infections affect the lower respiratory tract (lungs, air sacs) and the bird makes sounds that remind of coughing. In fact, coughing is not quite correct since birds are unable to do so. They don’t have a diaphragm and due to this difference in anatomy they can just make sounds that are a bit similar to coughing. On the left you can see a bird whose nose is severely infected, (a bacterial infection).

The birds can be short of breath and in severe cases they may suffer from choking fits that last for several minutes. Due to this, many feathered patients become too weak to perch on their branches. They totter on the ground instead or the bottom of the cage, desperately fighting to get enough oxygen while they breathe. Some birds try to help themselves by attaching their beak to the bars of the cage. This posture enables them to stretch their trachea and breathing becomes a bit more easy. Often one can hear a sound with each breath a bird takes that is typical for a respiratory infection. Also moving the tail feathers up and down with each breath and a “pumping” motion of the breast can be observed in affected birds.